Frey Finale

Defamer had a hilarious suggestion of Joey Fatone portraying author James Frey in the film version of the controversial memoir A Million Little Pieces. And on that note, I'm hoping this can be the last post on the Frey controversy for a while.

What Do I Think?

Good question. I've resisted weighing in with an opinion on this controversy until I could formulate some thoughts. And I'm still trying to detail those thoughts today. I read A Million Little Pieces when it first came out in April 2003. I'm looking at my first edition copy (think it's worth anything on the rare book market?) and I remember that the cover design caught my eye in the bookstore. The blurb from Bret Easton Ellis sealed the deal for me.

I swallowed the book whole and enjoyed it immensely. I've suffered through some pretty barbaric dental issues so the whole root canal scene had me quite literally sweating. After Oprah's selection, it became a popular game for the literary intelligentsia to criticize this book and the recent controversy puts even more of a bullseye on it. But I can't revise history and ignore the fact that I did enjoy A Million Little Pieces and did my best to promote this book long before all this stuff happened.

On first glance at the controversy, I say it's no big deal. Memoirists do this kind of thing all every single day. Sara Nelson, editor-in-chief of Publishers Weekly, wrote the following compelling argument.

This happens all the time, of course, and memoirists regularly get pilloried for it. (I remember complaints from Dave Eggers's family for some portrayals in A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius and even the sainted Frank McCourt was questioned about some of his recollections.) But memoirists aren't journalists, they're narcissists. They don't claim to tell the whole story; they're only really interested in their own. So I wonder about all those people who say they feel duped by James Frey. Would they have bought an earnest, footnoted academic treatise on alcoholism if it read like, well, an earnest, footnoted academic treatise on alcoholism? Somehow, I doubt it.

I must say that Nelson makes a valid point. But on the other hand, the whole controversy does raise some questions in my mind.

Where Does It End?

As I write this, on Sunday evening, James Frey occupies the number one spot on the New York Times bestseller list for both the Hardcover Nonfiction and Paperback Nonfiction. How do the other memoir writers on this list feel? Maybe they embellished certain aspects of their writing as well and they're just glad they haven't been caught. Maybe they played it straight and now they're pissed that they didn't follow the technique of "in certain cases things were toned up," as Frey told Larry King on CNN. This whole situation of embellishing facts for the sake of drama has the potential to progress like the steroid scandal in baseball. How does a straight player keep up? If that other guy is taking andro, do you stay natural or do you try to match him fire for fire. If that guy moves from andro to the powerful stanozolol, do you start cheating just a little? Where does it end? If we allow the memory is subjective argument and we believe that memoirs aren't straight nonfiction, then how far can the embellishing go?

One of my favorite nonfiction books is Mikal Gilmore's 1994 release, Shot in the Heart. In this compelling narrative, Gilmore reconstructs his family history to discover what caused his brother Gary to become a murderer. Shot in the Heart isn't so much a dry, only-the-facts recitation of Gary's story, but rather an examination of the family that produced a killer.

The American Heritage Dictionary defines a serial killer as "a person who attacks and kills victims one by one in a series of incidents." Now, Gary murdered two innocent people on two consecutive days. So by that definition, he was, in fact, a serial killer. However, when we discuss serial killers in this culture, we usually talk about Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer, John Wayne Gacy, and others of that ilk. We talk about all kinds of depraved acts and body counts in the dozens. Gary Gilmore killed a hotel manager and a gas station employee. Tragic circumstances, but not the gory, salacious details of Bundy hacking his way through sorority girls or Dahmer dining on his victims. So for most of us, Gilmore probably doesn't conjure up the same macabre atmosphere as those other monsters.

What if, in an attempt to embellish his story, Mikal Gilmore added a couple of victims onto Gary's tally? Maybe throw in a middle-aged waitress at a highway diner on a lonely stretch of Interstate 15? How about a teenage boy bagging groceries at the local supermarket so he can save up enough cash to pay for his tuxedo rental for the prom? Toss in some more murders, some sex, a dash of cannibalism, and Mikal could have had a much, much more salacious story.

And, even with those additions, the "underlying message" (to use the term Oprah utilized when supporting A Million Little Pieces in spite of the controversy) of Mikal Gilmore's Shot in the Heart would still remain the same. Remember, it's not a book about the facts of a murder. It's a book about a family that spawns violence. So he could embellish Gary's body counts, get a whole lot more attention, and still keep the same "underlying message."

Since Gary Gilmore was the first person executed in this country after the reinstatement of the death penalty, and the subject of the book The Executioner's Song, the case generated plenty of publicity. Mikal Gilmore could not have gotten away with embellishing the details of his brother's case so I'm obviously being facetious and extreme here, but hopefully you see my point. The underlying message of a family wouldn't change, so why not toss in a couple of extra corpses for spice?

What Can I Learn From This?

From time to time, I've pitched a memoir of life as an aspiring author. Numerous literary giants have penned memoirs about their writing life, but those stories are usually told from the remove of years-worth of publications and their names lining books on library shelves. They rarely capture the urgency, the despair, the exhilaration, and the frustration of what you and I feel. Look at Stephen King's On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft.

I love King's work and when he talks about nailing his rejections to the wall, I totally believe it and adore that image. There are many great tips in this book that serve any young writer well. But there are a couple of aspects of that book that I would argue reveal King's distance from the struggles of a contemporary aspiring author. King provides a cover letter from "Frank," a composite of several young writers King claims to know. He admits that Frank is fictional, but based in the experience of these actual people and he thinks "other beginning writers--you, for instance, dear Reader--could do worse than follow in Frank's footsteps."

King's sample cover letter from Frank mentions some short story publications and that he "would be happy to send any of these stories (or any of the half dozen or so I'm currently flogging around) for you to look at." Finally, in the next to last paragraph of the cover letter, Frank gets around to the real point of the letter. "The reason I'm seeking representation now is that I'm at work on a novel. It's a suspense story about a man who gets arrested for a series of murders which occurred in his little town twenty years before. The first eighty pages or so are in pretty good shape, and I'd also be delighted to show you these." Also in the cover letter, Frank mentions his age, his wife's name, the fact they've been married four years, that they teach high school, and that $500 lasts about a week in their bank account.

Frank sends this cover letter to a dozen agents. His letter to each is exactly the same, with only the salutation altered. Supposedly, three agents write back wanting to see some of the stories. Six agents ask to see the first eighty pages of the novel that "are in pretty good shape." One agent calls Frank to chat about his work. And only one agent expresses zero interest in Frank's work because his client list is too full.

Now, Stephen King's success and body of work speaks for itself. He's one of the most popular writers in the world and I'm a nobody. So maybe I shouldn't be questioning his judgment. But you tell me, when is the last time that you sent a cover letter to a dozen agents and received responses from every single one of them? When is the last time that you mentioned short stories to an agent and had several wanting to read them? When is the last time you, as a previously unpublished novelist, pitched a half-finished book with no title, no synopsis, no outline, and no plan for completing it and yet got six agents who wanted to see it?

Maybe I'm doing something wrong because Frank's experience ain't what I'm seeing at all. So I think there's a need for a contemporary book by a contemporary nobody about finding your way through the publishing world.

But ANYWAY (as Chuck K. would type it) this discussion is about what I can learn from the James Frey controversy (and even the J.T. Leroy scandal) to improve my work. Maybe the memoir I've pitched isn't interesting enough. Maybe instead of parents who just celebrated their 41 wedding anniversary, I should say I come from a broken and abusive home. Maybe I should insert some sort of time pressure. I could claim that I lost my job and that I have to immediately kick my writing career into gear if I'm to put food on the table for the five kids that I just made up. And on and on.

I could embellish all these details about my life, maybe make the backstory of my writing/publishing memoir more attention-grabbing, and still remain true to the "underlying message." Hell, I could work in some sort of disability or abuse or addiction or trauma and we could add on the terms "inspiring" and "recovery" to my memoir about writing.

On CNN, Frey pointed out that "the book is 432 pages long. The total page count of disputed events is 18, which is less than 5 percent of the total book." So I could toss in a beginning about how desperate my situation is and how I was born with half a brain, how my parents dropped me in a garbage can when I was three, how I became addicted to drugs at age six, how I supported myself by working as a gigolo for wealthy women at the country club, how I worked as a hitman for the Mafia, and then just focus on the writing and publishing experiences. As long as I stick to that percentage above, I'll be fine and remain true to the "underlying message."

Send in your suggestions for aspects of my life I can spice up while remaining true to the underlying message of my writing/publishing memoir. Let's see if we can get somewhere now.

No Real Answer

So I guess I'm not offering you any real answer or opinion on all this James Frey controversy. On one hand, I don't think it's a big deal. On the other hand, I think it raises significant questions about how much "embellishing" can occur and a book still be considered nonfiction. And I'm most concerned about what this means to you and me, our lives, and our identities as writers trying to get a book published.

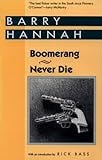

I'm reminded of one legendary story involving my mentor, Barry Hannah. Rick Bass recounted this tale in his introduction to the 1993 Banner Books edition Boomerang and Never Die: Two Novels by Barry Hannah.

In the wonderful introduction, Bass recounts the exploits of the "bad Barry." He mentions the alcohol, the gun, the shooting holes in a car, the saxophone riffs, the flaming arrows, all of it. But there's one story that Bass relates that is particularly appropriate to this discussion.

Another passed-down tale: a student getting her story back from Barry, with the honest criticism on it: This just isn't interesting.

As I understand it, the student, a whiner, complained, What can I do to make it be interesting?...

Barry, I am told, looked long and hard at the student, decided she was earnest about becoming a better writer, and told her the truth, told her Jack's and Homer's truth: "Try making yourself a more interesting person."

The student--as would have any of us--reportedly dissolved into tears. I know Hannah well enough to know that he was telling the student to experience life, to struggle, to succeed, to fail, to cry, to laugh, and do everything possible with her days on this planet. Those experiences would influence her writing to make it more compelling, more interesting.

But, with the controversies surrounding James Frey and J.T. Leroy, we can take Hannah's advice on a more superficial, more personal level. My writing/publishing memoir project may not interest anyone as it currently stands. But if I can make myself a more interesting person, "tone up" my backstory so it includes something that's not true, that might make all the difference in the world. Or maybe I should get an actor to portray me in public. Hannah didn't mean it this way, but maybe it is about who is the most interesting. We've always suspected this, I'm not naive about the nature of publishing and marketing and all that. But these controversies put a new light on it entirely.