Who Knew It Sucked So Bad to Be a Published Writer?

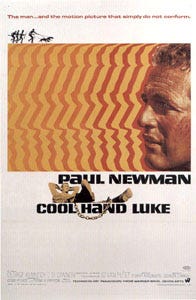

I had no idea. All these years, I thought Cool Hand Luke was just a fantastic movie from 1967. I had no idea that it's actually true and that Strother Martin's character, The Captain, was not a prison warden but actually a Creative Writing Department Chair. You too? Well, you had it wrong, just like me. He's actually talking to writers when he instructs the new inmates writers that "You gonna fit in real good, of course, unless you get rabbit in your blood and you decide to take off for home. You give the bonus system time and a set of leg chains to keep you slowed down just a little bit, for your own good, you'll learn the rules. Now, it's all up to you. Now I can be a good guy, or I can be one real mean son-of-a-bitch. It's all up to you."

It seems to be fashionable recently to bitch about being a writer. The annoying gnats of adoring fans, the misery of teaching creative writing, the hoard of locusts who want a recommendation or a blurb.

A Carton of Cigarettes for Your Grad Assistant

In the July issue of Harpers, Lynn Freed has an essay called Doing Time: My Years in the Creative Writing Gulag. It's worth belaboring a bit of the obvious in this title. Merriam Webster defines gulag as "the penal system of the U.S.S.R. consisting of a network of labor camps." Teaching creative writing is a job, like any other, with good days and horrid days. But I've been in a number of writing professors' offices oops, I mean cells over the years and I've never seen vertical lines carved into the plaster with a sharpened spoon, marking time until parole. I've never seen a creative writing teacher shanked with a chicken bone and I've never seen them eat dishwater-like gruel out of a tin bowl with some stale bread.

Freed, author of Bungalow: A Novel, Homeground, The Mirror, Friends of the Family, House of Women: A Novel, The Curse of the Appropriate Man, and the forthcoming Reading, Writing, and Leaving Home: Life on the Page goes on in the article to detail her prison sentences while being forced to accept money for teaching a class. Years after leaving behind an unfulfilling stint as a professor, Freed returns to the academic world by accepting an invitation to teach at a large university in the Southwest. "This time there hadn't even been a question of what I really wanted: I needed money." She finds herself back on campus and wonders "had marriage been this bad?"

Freed had attempted to carve out a life as a part-time travel agent and writer, balancing fiction and freelance writing with journeys here and there. Teaching was something she resorted to in order to pay the bills although she wonders "what my writing life would have been like had I become a lawyer. Lawyers certainly could work part-time" and write with the rest of their day. Later, Freed revisits this same type of fantasy when she "wondered if things would have been easier had I become a doctor. Doctors certainly could work part-time." I'm sure internists and residents all over the country, coming off a 16 hour shift saving lives will relax and breathe easier knowing that Lynn Freed insinuates that teaching a creative writing class is more draining, for her at least.

After a series of part-time and temporary teaching assignments, Freed was "tired of struggling and longed for what I could only think of as peace. It had been ten years since I had taken that first creative-writing job in the Southwest, and I was tired of moving; tired, too, of worrying where the next job would come from and where it would take me," so she accepts a permanent half-time professorship at a large university within easy reach of her home. Almost immediately, she blanches at having to promote the department to prospective students and she quivers at the repulsion of having to name which writers she admires because "my reading of contemporary fiction is spotty at best."

Left out of the essay is undoubtedly the captains and bosses of the department's admonishments of professors who don't toe the line. "Your grades are due within a week of the end of the semester. Any teacher late with his grades spends the night in the box. These here grade sheets, you keep with ya. Any teacher loses his grade sheets spends a night in the box. There's no playin' grab-ass with any students. Any teacher playin' grab-ass with students spends a night in the box. First bell is at five minutes of eight... Last bell is at eight. Any teacher not in his classroom at eight spends a night in the box. I'm Carr, the floor walker. I'm responsible for order in here. Any teacher don't keep order spends a night in the box."

Perhaps it's telling that Freed doesn't name any of the universities in her essay since that might be too obvious, too noticeable, to hard for taxpayers and alumni to ignore. As the essay stands, readers can pretend to not know where Freed is collecting her paychecks, but if she named the institution, it might make for difficult times in the department office since she says "if there are teachers who know how to work from the abstract to the concrete, I am not one of them" and "the happiest teachers are, perhaps, those who are most comfortable in the role of parent or mentor. I am neither. I might advise a good student to get himself out of the academy as quickly as he can, but I have no stake in his future beyond wishing him well." Her students, paying her salary, have a difficult time accepting it when she tells them "at the outset, even though they will not believe me--why should they?--that, to my mind, writing cannot be taught. That workshops can be dangerous." In small doses, there are some truths to Freed's points. A workshop cannot teach the discipline to sit in the chair, for hours, weeks, and years after the workshop is over. A workshop can teach the craft, but maybe not genius. Workshops are useful, I would argue, but they aren't miracles. Yet, Freed's solid points are lost in her agony.

After all the complaints of the misery in the creative writing department, Freed talks about how several times she has returned to the classroom, after a semester or year off, "angry and full of blame. And yet, whose fault is it if I have made this bargain? My parents', for not having had the wherewithal to leave me a trust fund? My husband's, for departing an unendurable marriage? My own, for not having had the courage to trust my writing to see me through?" Tellingly, Freed never explicitly answers that question, never admits her own responsibility in accepting the university checks.

Agoraphobia for Poets

I might have taken the bait, fallen for the Orson Welles radio show, and revealed myself to be one of those people who actually believe that Bill Gates will give me a fortune for forwarding an email. But since this comes so close to so many other articles detailing all the complaints, I'll treat it as real and not a spoof for the Humor Issue. Maybe she's satirizing the complainers but these days, who can tell?

In the July/August 2005 issue of Poetry, Kay Ryan details her experience attending the Association of Writers & Writing Programs Annual Conference (AWP). Ryan suffers from physical maladies at the experience of doing anything with anybody. "I have never taken a creative writing class, I have never taught a creative writing class, and I have never gone, and will never go to anything like AWP" she writes, emphasis is hers. She relates a story when in her younger years, she did foolishly dip her toe into a writers conference and "thirty minutes into the keynote address I had a migraine. It turns out I have an aversion to cooperative endeavors of all sorts." But now, years later, and presumably armed with stockpiles of Almotriptan and Iso-Acetazone to treat any pesky migraines, Ryan accepted an invitation to attend AWP as an outsider and write a piece for Poetry.

Author of the poetry collections Say Uncle, Elephant Rocks, The Niagara River, and others, Ryan frets about the effects attending the conference may have. She worries that she will begin to see the attendees as real live human beings, nice people, unique individuals. She despairs "how am I going to remember: these people are the SPAWN OF THE DEVIL?" Once again, the emphasis is Ryan's.

Ryan does discuss some admirable reasons for her disdain of writing classes, organizations, and conferences. She prefers that the works stand on their own merit, "no networking, no friends in high places, no internships. I think that's how poems finally have to live, alone without your help, so they should get used to it." Hard to argue with that line of thinking. And admittedly, Ryan does seem to acknowledge that maybe she is the unusual one, maybe she is the one with the unique personality. She seems to try to give the conference a fair shake and she seems more than willing to admit her own quirks in this situation.

But, Ryan still finds it hard to believe that anyone might actually get something out of the fellowship of other poets. Her mouth seems to drop open in shock when she attends a presentation and notes that "a number of panel members, with members of the audience nodding in agreement, say that they are actually nourished by student work, and stimulated to do their own work. I am speechless."

She enjoys a lunch with a couple of fellow poets and even wonders why, if this meal is so enjoyable, she doesn't seek out such company more often. But when one of her friends mentions trying to find an arc for his collection she writes "already it is coming to my why I don't have more of this camaraderie; just the thought of vogue shapes for poetry books oppresses like cathedral tunes... The more I think about it, the more oppressed I feel -- so many of us writing books of poetry, with or without an arc. How in the world can I feel really, really special?" Reading this section, I'm reminded of the kids in high school that did very well, but they didn't want you to think they actually tried. I can imagine Ryan and other poets standing around in the hall, after grades have been posted, and someone says "Wow, Kay, you really aced that test," and Ryan sneers "yeah, you know, I slept through the whole arc discussion, I mean who cares you know? That's just lame."

At the conference's grand finale, a reading by Anne Carson and W.S. Merwin, Ryan dismisses the large scale of the reading. "The room is all out of proportion with how poetry works. The pressure is all wrong. This place is right for revivals and mass conversions, for stars and demagogues. I don't think I'd trust poetry that worked too well here. Aren't the persuasions of poetry private? To my mind, the right sized room to hear poetry is my head," she writes.

On the flight home from the conference, Ryan has the unfortunate experience of sitting next to a fellow poet, a fellow conference goer, and God forbid, an admirer. A young lady seated next to Ryan on the plane exclaims how happy she is to meet the more established poet. The young woman even taught one of Ryan's essays in her class. Later, Ryan and the admirer sit on a bench outside the terminal, waiting for the airport shuttle, and the poet recalls the moment as "Oh God, wasn't this just the perfect illustration of everything I hated? What in the world was this lovely, unfledged creature doing teaching a creative writing course? And what in the world was my essay doing encouraging these ever expanding fuzzy rings of literary mediocrity, deepening the dismal soup of helpful, supportive writing environments?" Who knew the horrors of having your work appreciated and shared?

Luckily for us, and poetry admirers everywhere that have the temerity to like someone's work, Ryan proves her sense of humanity by ending the essay with the scene on that airport bench where she proudly proclaims "No, I didn't even struggle in my chains. Instead I felt pleased that my essay had proven useful, and flattered to be recognized, and wanted very much to be likeable in person." An admirable ending, but two sentences hardly alter the tone of the overall piece.

No Wonder People Want to Stick With Boy Wizards

Maybe I'm just in a pissy mood. Maybe these articles come too close on the heels of my rant about the Kaye Gibbons article in the Winter 2005 issue of The Oxford American where she described the aspiring authors who pay to attend conferences and hear her speak as a "plague" when they ask questions she deems insignificant and unworthy. But am I missing something here? Are these writers employing some ironic and sarcastic techniques in their writings that are just going over my thick-head? Am I the type of knucklehead that would have thought Jonathan Swift was serious? Or is it really that bad to be a published writer for these folks?

In Lynn Freed's case, she gets half the year to write and teaches for the other half... and that's the equivalent of a labor camp to her? Notice that it's not enough of a torture to get her to give up the paychecks she cashes for something she doesn't believe is possible.

I taught a junior-level course as part of my graduate assistantship. And I've done a lot of teaching and training in the corporate world as well. That's not an entire career, no, but it's enough that I know teaching is difficult; being on camera, being tested, maintaining order and respect. The old saying that "those who can, do and those who can't, teach" is insulting bullshit. But at the same time, I've also shoveled horse shit all day long in a barn with a tin roof on in it in the summer. I've crawled under the eaves and rolled out that pink torture called insulation in 95 degree heat. I've loaded hay bales and I've washed dishes in restaurants. And let me tell you, I'll take Ms. Freed's teaching gig any time over those endeavors.

As I write this, 93 degrees outside and the humidity is high enough to make it feel like it's over 100. The National Weather Service has issued heat advisories for the area and as I walked to get a sandwich, I saw a crew out in the heat, laying blacktop on a section of road. I stopped to tell them they should be glad they don't teach creative writing but they weren't amused. There was a street musician strumming an old guitar and I told him "be glad, no one likes your work! No one will ever want to teach your work in a classroom," but he wasn't listening because was too focused on shaking the chewed up coffee cup for change.

I saw the Bon Jovi video for Wanted Dead or Alive, I know that the reality isn't as glamorous as it seems, I know that even dream jobs can be mind-numbing and soul-destroying at times. But with writers publishing high profile articles complaining about having to teach, complaining about having people tell you they like your work, complaining about having to answer questions from fans, is it any wonder that so many people in this country are turned off by serious literature and they turn to boy wizards and religious conspiracies for their literature? At least J.K. Rowling and Dan Brown have the respect, or manners, or whatever to stay out of the public eye. They may dislike their jobs as much as the writers discussed here, but at least they keep quiet about it.

I'm sure the authors I'm dissecting here are nice people and they're certainly wonderful writers. Maybe they just needed to blow off some steam. I've certainly met some wonderful people who don't think you can teach creative writing and many of them are employed in those positions. But to cash a check for a publishing an essay where you complain about cashing a check for something you don't think is possible? That's just wrong.

We all complain about our jobs. Professional athlete, brain surgeon, porn star, famous musician, cabana boy, it really doesn't matter. Everyone, at one time or another, hates their gig. But does that mean we have to publish their articles and their essays? I mean, it's bad enough that Freed is filling a position teaching creative writing when she doesn't think creative writing can be taught and keeping someone else, who does believe in the endeavor, from it. Do we also have to award her a coveted spot in a prestigious magazine bitching about it and rubbing everyone's face in it? Do we have to reward people who scoff at their industry, who refuse to take part, who claim to suffer physical maladies (even if it's a joke) at the thought of having to play with others?

I share with many others the frustration at the fact that everyone seems to think they can write a book. Is this attitude being expressed in these essays some sort of retreat? Are these authors trying to mystify their craft so they can claim some direct line to the muse that mere mortals don't have? Is Ryan's point that she's just somehow so innately talented that she doesn't have to be bothered thinking about an arc to her poetry collection? Or does she think it's just impolite to discuss such nitpicky mechanical details?

Sour grapes on my part? Jealousy? Damn right. I'll admit to those petty emotions. I complain at times about the publishing industry because we're trying to reach the point where these writers are. But these articles rub me the wrong way because I know that I, and many others, would love to be in the box with Freed and Ryan, talking shop and discussing story arcs. That's what this site is about. We do this in our spare time, in addition to working fulltime jobs and also writing. You read sites like this in addition to your busy schedules. If Freed and Ryan and people like that don't want to participate, if they just want to stay safely ensconced in their garret, protected from the philistines and the riff raff that does want to learn technique, that's fine. To each his own. But why complain about it?